Flogfactoring

November 29, 2012 | 7 minutes (1409 words)After checking in with Micah this morning, I was given my task for the day: achieve 100% test coverage for my Ruby tic tac toe program and get every method’s Flog score under 20. I was sitting at about 96% test coverage to start with, and I only had a few methods that had Flog scores greater than 20, so I thought this won’t take long. I’ve learned over the past 6 months that whenever I think “this won’t take long,” it always does.

To get warmed up, I decided it would be good practice to write another Minimax method without referring to my previous attempts. The first time I attempted Minimax back in July, it took me several days. The second dance with Minimax was a day. This third dance took about 30 minutes. It was enjoyable working through the problem again with the understanding I’d gained from the previous two attempts. I’m thinking that Minimax might make for a nice code kata, but I want to try a traditional code kata first.

After the warm up with Minimax, my mind was steeped in the problem and I was ready to attempt refactoring my alpha/beta pruning minimax method. I started playing around with how to split apart the various steps of the algorithm so I could encapsulate them in their own methods. The most difficult part of this was managing all the values that needed to be passed and returned. I thought invoking method after method with five or six paramaters looked gross, so I opted to create a hash and pass the required values as one paramater. This approach helped me abstract some of the responsibility of specific steps of the algorithm into their own methods and I achieved a Flog score of 18. But, I wasn’t satisfied. For one, the hash structure feels fragile. If I mispell a key and try to extract that value out of the hash in a method somewhere in the algorithm, it can be a difficult error to locate (extracting a key that doesn’t exist from a hash in Ruby returns nil). I also didn’t like the code’s aesthetic. Here’s a portion of the hash implementation:

def eval_score(state)

if state[:max_player] && state[:score] > state[:alpha]

state[:alpha] = state[:score]

state[:best_move] = state[:index]

elsif !state[:max_player] && state[:score] < state[:beta]

state[:beta] = state[:score]

end

state

end

This makes me cringe. Having state[:key] everywhere throughout the method is hard to read. Alternatively, I thought I could set each value needed at the top of the method in local variables:

def eval_score(state)

max_player = state[:max_player]

score = state[:score]

alpha = state[:alpha]

beta = state[:beta]

best_move = state[:best_move]

if max_player && score > alpha

alpha = score

best_move = index

elsif !max_player && score < beta

beta = score

end

end

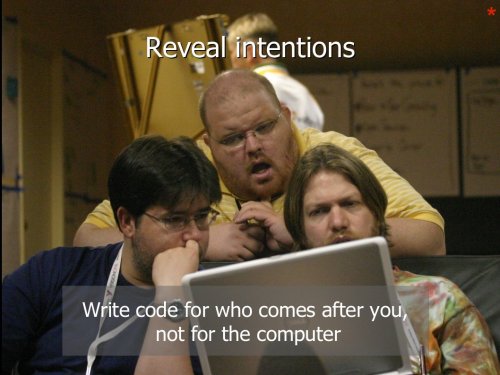

This also makes me cringe. This bloats the method, stretching it out and would require another developer to sift through the initialization of a series of local variables before getting into the logic. There’s also the issue of deciding how to return the values. If I’m passing around a hash, that means I have to reassign the new values from my local variables back into my hash, further adding to the length of the method. That just isn’t going to work. Part of the desire to learn how to write clean code is to minimize the pain of revisiting the code in the future and making changes not just for me, but for anyone that might potentially read my code. Otherwise, we might end up with this situation:

<div style="width: 500px; margin: auto;"> </div>

</div>

So I thought, hey I’m in a class, why not offload some of the values I need to pass to different parts of my Minimax algorithm via instance variables? I realize now that this approach is also problematic, because most of the values needed for the Minimax recursion to work properly require them to be defined in their calling environment, and not on the instance of the object passing and receiving messages related to the Minimax algorithm. This is because when I’m returning through the call stack, I depend on certain variables maintaining the value they held in the context of that invocation. Otherwise, I end up clobbering those values and losing the benefit of using recursion in the first place.

In light of that revelation, I resolved to using one instance variable to keep track of the best move found so far. I also tried to split apart the various steps of the Minimax procedure in divisions that seemed to be the most logical. I didn’t fully succeed in this, as I have a method that generates the game trees and scores them, and could be considered a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle (applied to methods). My justification for this was based more on the nature of the algorithm, rather than a lack of ambition. I considered how I could split creating the game tree and recursively calling the Minimax method for each possible next move, but decided that it would add more complication and possible confusion for another programmer.

In the end, my final refactoring I think is too dense and harder to understand despite its Flog score of 12:

def minimax_with_alpha(max_player = true, ply = 0, alpha = -9999, beta = 9999)

return(board.winner? ? winning_score(max_player, ply) : 0) if base_case_satisfied?

alpha, beta = gen_score_game_tree(max_player, ply, alpha, beta)

return( ply == 0 ? best_move : max_player ? alpha : beta )

end

I think expanding out the first line, to avoid the use of a nested ternary operator is a good idea. Not listed are the abstractions I created for stepping through the game tree and for scoring the moves, which represent the real heart of the Minimax algorithm. I leave the code in this form, not because I think this would make for good production code, but because this is what made Flog happy. I think in general the Flog analysis was good for identifying methods that seem long and unwieldy, but I recognize my current ability is not quite grasping how to more effectively abstract methods in order to maintain readability and brevity. In this case, I thought refactoring based on Flog should be called Flogfactoring, because in cases like this, when the algorithm used to create the Flog score isn’t that sophisticated, it seems to reward very dense and compact code that is hard to read - and ironically really flogging the mind of another developer who might try to read this in the future and muttering profanity at me for leaving code like this behind.

Other highlights of the day include another game of 5 0 chess with Paul Pagel. I’ve been playing with a variation of the Sicilian Opening. Because I’m not very familiar with the common patterns of this opening, I extended a few pieces too quickly and Paul’s positioning took advantage of this. I then switched strategies seeing that we were equal materially and decided to swap a series of pieces in rapid succession to get to the end game. I love the end game in chess. When the action settled, Paul graciously offered a draw, despite his two pawn advantage. The speed of a 5 0 game is something I’m not used to, but it is an exciting way to play chess. To really push the brain, it is fun to play 1 0 chess (the 1 means each player has a minute total to make their moves, the 0 means each move made adds 0 seconds to the player’s total time remaining).

Tomorrow I’m very excited for 8th Light University which features a talk by Uncle Bob. He’s a living legend in the programming world, and after watching a few of his talks via YouTube, I can’t wait to see him speak in person! I’m also looking forward to my first afternoon Waza, a time when all the Chicago 8th Light developers come to the downtown office and code on personal projects, open source software, in-house projects, or pair up with other developers and find out what they’re working on. I’m planning to do some pairing with Anish Kothari, another apprentice, who is also working on solving tic tac toe with Minimax. What an amazing way to end my first week at 8th Light!