Building SOLID Foundations of OOP, Part 1: SRP

December 03, 2012 | 5 minutes (968 words)Over the weekend Micah asked me to write a UML diagram of my Ruby tic tac toe program, and review the SOLID Principles of Object Oriented Design. This morning I went to the Libertyville office and had the great opportunity to “teach” Micah SOLID, and also review my UML diagrams. As a former teacher and teacher trainer, I really appreciated Micah’s approach in asking me to explain the principles to him. In doing so, it highlighted all the areas where my understanding of SOLID was not solid, and it also allowed us to talk about SOLID in relation to the tic tac toe program, which I found immensely helpful. There’s a lot that could be said about both UML and SOLID, but this week I’d like to review the SOLID Principles. Each day I’ll devote a post to one of five SOLID principles to further help cement my understanding and also provide anyone who is starting out with these ideas a simple introduction.

So, what is SOLID?

Single Responsibility Principle

Interface Segregation Principle

Dependency Inversion Principle

In this first post, let’s take a look at SRP.

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

I found this principle to be easiest to immediately understand and describe. Every class, method, module, component or other segment of code should have a single responsibility. A good way to measure whether or not a class or method contains more than a single responsibility is to try to describe what that segment of code is doing. If our description requires us to make a list of its responsibilities, we know we’ve missed the mark.

Let’s say we have a CheckingAccount class. It keeps track of the checking account owner, balance, account number and routing number. Behavior defined on this class allows us to deposit and debit funds to and from the account.

class CheckingAccount

attr_accessor :owner, :balance, :account_num, :routing_num

def initialize(options)

self.owner = options[:owner]

self.balance = options[:balance]

self.account_num = options[:account_number]

self.routing_num = options[:routing_number]

end

def debit(amount)

self.balance -= amount

end

def deposit(amount)

self.balance += amount

end

So far so good, our CheckingAccount class seems fine. We have defined a few simple behaviors on CheckingAccount, but nothing that seems to violate SRP just yet.

The next morning at an iteration planning meeting, a new user story is slotted to be completed on the next iteration. The user story looks something like this:

As a CheckingAccount holder

I want the ability to schedule automatic withdrawals from my account to pay bills.

Eager to tackle this first user story for the next iteration, it might be tempting to add some new methods to our CheckingAccount class:

class CheckingAccount

attr_accessor :owner, :balance, :account_num, :routing_num

def initialize(options)

...

end

def debit(amount)

self.balance -= amount

end

def deposit(amount)

self.balance += amount

end

def new_monthly_payment

...

end

def verify_monthly_payment

...

end

def schedule_monthly_payment

...

end

def make_monthly_payment

...

end

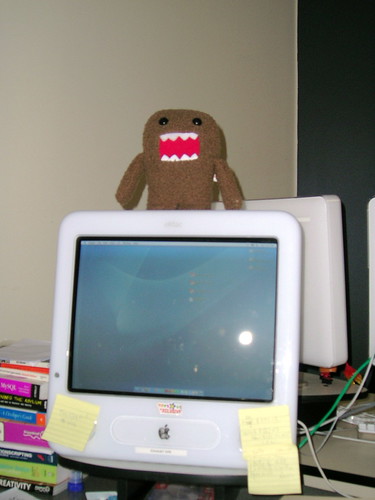

After adding just four methods, this code is really starting to smell. What does #verify_monthly_payment have to do with our checking account? Sure, it’s related, but only by association. Our checking account doesn’t need to know about the verification of a monthly payment, it just needs to be told when to debit and deposit, so it can tell us the balance. CheckingAccount has become polluted with additional responsibility that muddles its single responsibility, and adds extra responsibility that is ill-defined in the CheckingAccount class context. If we were to continue defining the monthly payment behavior in CheckingAccount, the numerous methods required would quickly overwhelm CheckingAccount due to the requirements of the problems associated with scheduling, dealing with dates, verifying payments, user input and forms, etc. Our once simple class has grown into a class monster, reminding us of this very important fact: ###Everytime you violate SRP Domo-kun pops out of your computer and eats a finger.###

<div style="width: 275px; margin: auto;"> </div>

</div>

How do we save our precious fingers? Make a new class!

class CheckingAccount

def initialize(options)

self.monthly_payments = options[:monthly_payment_collection]

...

end

def debit(amount)

...

end

def deposit(amount)

...

end

end

class MonthlyPayment

def initialize(options)

...

end

def new_monthly_payment

...

end

def verify_monthly_payment

...

end

def schedule_monthly_payment

...

end

def make_monthly_payment

...

end

...

end

This looks better. We have achieved better encapsulation of the MonthlyPayment behavior and data in its own class, where it rightly belongs, apart from our simple CheckingAccount class. Not only is this easier to conceptually deal with, it also makes tracking down bugs easier, and we also maintain the ability to now configure multiple types of Monthly Payments on a single CheckingAccount. It’s a new piece of data associated with our CheckingAccount, so it seems justified to add a MonthlyPayment object as an instance variable to our CheckingAccount without CheckingAccount needing to know anything about how MonthlyPayment implements its behavior.

While SRP is commonly introduced in the context of classes, it’s important to remember that SRP can be applied to any segment of code, especially methods or functions. When we do this, we realize it’s best to avoid long, unruly methods, just as we have seen it’s best to avoid long and unruly classes. Abstraction is one of our best friends in the world of object oriented programming, and SRP helps remind us when new requirements come in to create new abstractions rather than force-fitting everything into one class, one method, one component, etc…(and because we’re honoring SRP and not being assaulted by class monster Domo-kun, your fingers will like you better too)

</div>

</div>